Microsoft Office macro-malware warnings have failed users

- 10 June, 2016 09:44

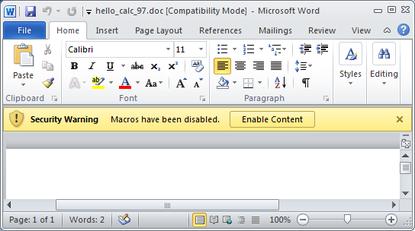

Office 2010: What would you click: "Macros have been disabled" or "Enable content"?

Microsoft may have ramped up efforts to combat macro-based malware, but one researcher argues that the warnings it gives Office users has put them in danger.

Macros are used to automate repetitive office tasks, but the capability in Office is being exploited on a grand scale to distribute banking malware and ransomware. Microsoft has issued several warnings about macro-based malware over the past year and even added a macro lockdown feature in Office 2016 to answer the rising threat.

Macro-based malware aimed at Office applications went out of fashion a decade ago after Microsoft turned macros off by default, but Microsoft may be partly responsible for its resurgence due to its security warnings when users encounter attachments that require the feature to be enabled.

Will Dorman, a vulnerability analyst at Carnegie Mellon University’s Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT/CC) says Microsoft’s poor security warnings after Office 97 have encouraged attackers to exploit it.

“The default behavior of Microsoft Office has usually allowed for inadvertent execution of malicious macros, but recent versions of Microsoft Office make it much easier for the user to make the wrong decision,” Dorman writes in an analysis of Office macro-based malware.

Dorman's retrospective of Microsoft Office’s macro warnings going back to the Melissa virus, which spread like wildfire on Windows PCs in 1999, and used a macro inside a Word document and propagate itself via email to promote porn sites.

Dorman characterised macro-based malware as a Microsoft design flaw and argued they're attractive to attackers because they're easier and more reliable than software vulnerabilities.

“Design weaknesses are a much more valuable target for an attacker, as opposed to an implementation flaw that relies on memory corruption, for example. The benefit of such weaknesses is that they can work universally,” he explained.

Recent macro-based malware is distributed by email with an Office attachment and a cue that entices the recipient to enable macros. Once enabled, the macro-based malware can effectively execute malicious code natively on the machine.

To demonstrate Office macro warnings between Office 97 and Office 2013, Dorman wrote a proof of concept macro for Word that launches calc.exe.

As Dorman highlights, macro warnings in Office went from “pretty clear” in Office 97 to non-informative by Office 2010. Back in Office 97 the dialogue box said: “The document you are opening contains macros or customizations. Some macros may contain viruses that could harm your computer.

In Office 2010 the warning moved to a message bar on a yellow background below the shortcuts to fonts and editing features. Additionally, the warnings appeared to encourage the user to enable macros. The same style was retained in Office 2013.

Office 2010’s warning states in black text on a yellow background: “! SECURITY WARNING. Macros have been disabled.” Confusingly, within the same yellow space is a highlighted box with “Enable Content” inside.

“The user is not given any information about the consequences of enabling macros, and the user is given only one obvious option: enable macros. This is dangerous. Attackers are using several social engineering techniques to convince users to click the "Enable Content" button as well,” wrote Dorman.

On a second pass at Office macro warnings over the years, Dorman discovered that Microsoft had actually made the phrase “Macros have been disabled” in Office 2010/2013 clickable. If the user does click, a more definitive security warning appears in a dialog box, along with an explanation of the risks, and links to support notes.

Still, Dorman argues the basic security warning is not obviously clickable and sits next to another box — “Enable content” — that invites the user to click it.

“This information is hidden far enough away from the "Enable Content" button that I suspect not many people would even see it,” he notes.

Dorman has a number of useful recommendations for the enterprise to contain the risk of macro-based ransomware. For one, generally few users in an organisation actually need to enable macros. Where that’s the case, admins should limit macros to users that required it and only allow signed macros.