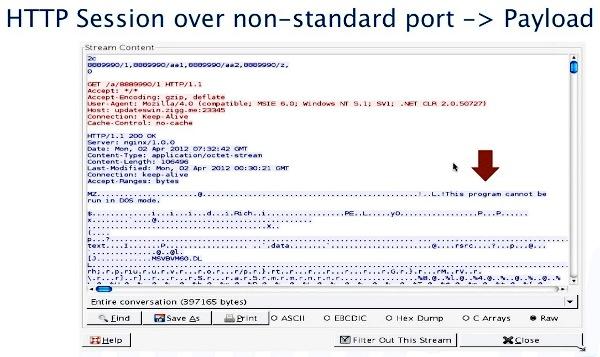

Traffic analysis often reveals telltale signs – such as this decidedly non-HTTP Web traffic – that a data stream includes malware.

The behaviour of IP port-hungry applications like Skype and BitTorrent reflect the type of evasive behaviour that is increasingly being deployed as malware employs ever trickier tactics to avoid detection by conventional firewalls, Palo Alto Networks global senior security analyst Wade Williamson has warned.

Analysis of application behaviour across 3000 live networks showed, for example, that while the industry-standard port assigned to Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) connections is IP port 443, applications were in fact setting up sessions using that protocol across nearly 5000 other ports.

Noting that Skype and BitTorrent can communicate over up to 20,000 IP ports at a time, similar port-crossing behaviour was noted for a broad range of IP protocols and applications; fully 260 different applications and protocols, Williamson said during a recent Webinar entitled ‘How to detect and stop modern cyberattacks’, had been observed tunnelling one type of traffic through a different IP port.

“This isn’t just limited to SSH [Secure Shell] and SSL,” he said. “You see tons and tons of applications that can do that. And because you have ports that will be open all the time, we now need to be concerned about what types of additional traffic might be cloaked and carrier through these ports. There should be a very, very limited number of places that you’re going to accept content from the untrusted Internet.”

While some uses these may be legitimate – peer-to-peer services, for example, use large numbers of ports simultaneously to transfer many blocks of data at once and ensure resiliency if an individual connection is lost – others indicate that malware authors are trying to circumvent normal port-based protections by sneaking their traffic into enterprises through the proverbial side door.

Another study of FTP protocol usage found applications pushing FTP traffic across 237 random ports, while even standard Web browsing traffic – normally confined to Port 80 – was observed across 90 different non-standard ports.

“We see custom Web tunnels that are purpose built to punch through your firewall or your security,” Williamson said. “When you see these things it’s almost always a dead giveaway that someone is trying to get around your security.”

Some of the malware Palo Alto has observed uses normal, typically unfiltered ports for occasional and innocuous communications, but retreats into the non-standard port region when it wants to transmit large payloads or those likely to be spotted by security tools.

Anonymiser services are frequent users of such attacks, with traffic shunted through a series of port-forwarding proxy services that expand their port profiles. But this technique is also appearing in malware, with the notorious TDL4 malware including its own supporting services including a proxy server.

“Even if a server went away, it had enough logic to find an infected host by talking to this peer to per network,” Williamson said. “This made it very reliable, and able to compensate and deal with the takeover attempt.”

Companies can minimise their risk from port shenanigans with policies mandating the use of specific applications known to behave in a predictable and consistent way with regards to their traffic handling.

Access to peer-to-peer or RDP services should be controlled on a per-user basis, while granular encryption – for example, encrypting traffic to social media or Web-mail services while blocking encryption of other types of traffic – can help keep visibility high. And, no matter the protocol, downloading of files should be tightly restricted to only those applications where it’s needed.

“These things aren’t necessarily going to be every time we see them, but we need to have context,” Williamson said. “Anything that can transfer a file is a potential vector for new malware, or a potential exit point for confidential data leaving our environment. We need to know we’re going to look into other tunnels and know how many ports are in use, and so on. It doesn’t need to be a threat.”

Follow @CSO_Australia and sign up to the CSO Australia newsletter.